Letter to Boat Owners – Below please find a link to a letter from the Contractor providing additional information and guidance for the claims process. Also directly below the letter there is a link to the current claim form.

There are many reasons why the 11th Street Bridge was renamed to honor Murray Morgan. That he was the bridge tender in his early thirties is part of the reason, but it is not the only reason. Like the bridge itself, both were central to the story of Tacoma’s development. He was born in Tacoma three years after the 11th Street Bridge was constructed and died here in 2000, three years after it was named in his honor. Both symbolized urban life and the city’s history. For many years, the bridge was the only non-rail transportation link between Tacoma and the port-industrial area. Its crossing over the Thea Foss Waterway was a constant hub of activity. So too was Murray Morgan’s writings, journalism, and teaching a hub of activity over the years as he reported on City Council meetings and wrote his own history of Tacoma. The history around the bridge is presented below. (1956 Photo: Tacoma Public Library Richards Collection D96799)

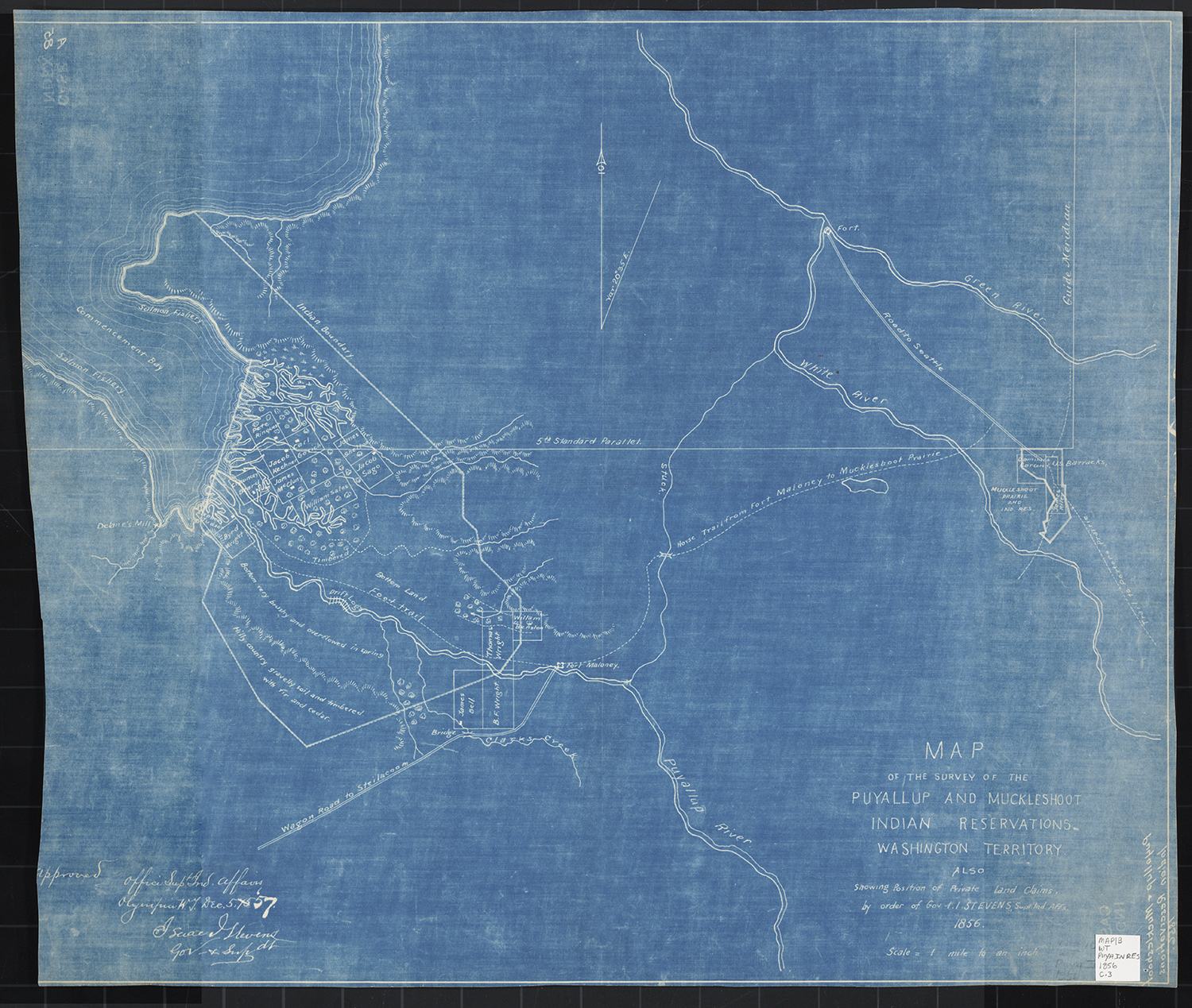

In 1856, Territorial Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Isaac I. Stevens ordered a survey of both the Puyallup and Muckleshoot Indian Reservations. The Puyallup Tribal boundaries are shown on the left side of this map produced in 1857. For the remainder of the 19th century these boundaries governed how Tacomans could develop industries and shipping wharves along the south shore of Commencement Bay and within the Puyallup River delta. (Washington State Historical Society map collection)

The development of New Tacoma began in 1873 when the Northern Pacific Railroad began to construct its terminal wharves along Commencement Bay. In order to expand a rather limited shoreline the rail company began to create what became the Thea Foss Waterway. Damming one arm of the Puyallup River was the first step in the endeavor. The Northern Pacific also extended a rail line from its wharves on the bay to the Pierce County coal fields and in the process constructed the first bridge across the waterway. Most early maps show the 9th Standard Meridian that was the boundary between Pierce and King County until c.1903. This governmental decision affected how industries and shipping facilities could be developed in Tacoma. (U.S.G.S., 1888)

In 1890, Tacoma photographer Ira Davidson worked his way onto the Puyallup River delta to document the Tacoma skyline. The only bridge seen off in the distance is the railroad line to the Pierce County coal fields. Above the structure is the Tacoma Hotel, opened in 1884. Little excavation work had taken place along the Thea Foss Waterway by this time, but the beginning of what would become the Wheeler-Osgood Waterway is shown in the foreground. This is the waterway formed when the Northern Pacific dammed the Puyallup River.

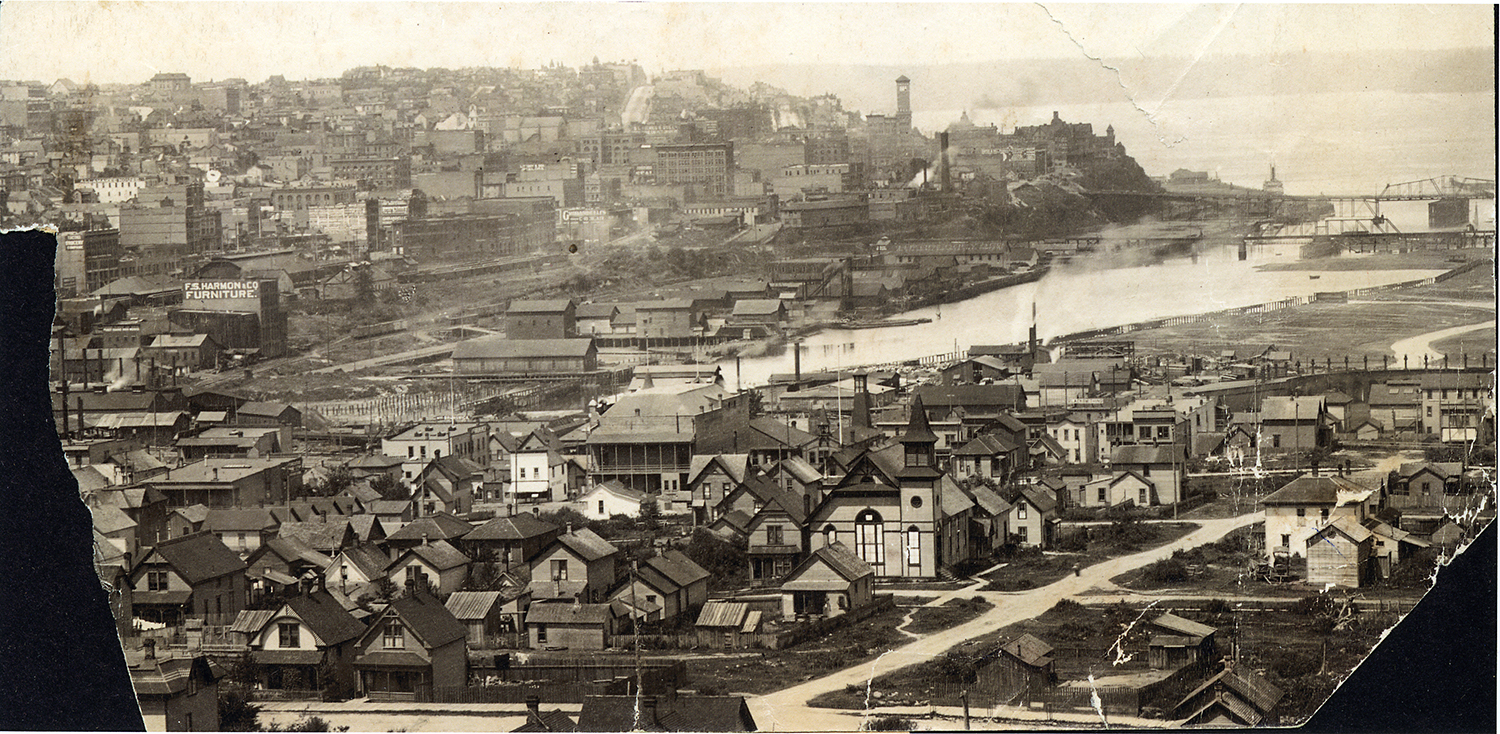

It took an act of Congress to complete the dredging of the Thea Foss Waterway when it authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to complete the project during the early years of the 20th century. Until that time work was funded by the Northern Pacific Railroad. By c.1894 there had been sufficient dredging to create the basic configuration of the waterway, and the first 11th Street Bridge had become a part of the city skyline. The Hawthorne neighborhood, located where the Tacoma Dome now sits, began as a development to house workers working on the east side of the waterway prior to the construction of the bridge. (Tacoma Public Library General Photograph Collection G17.1-074)

Tacoma’s waterfront development during its early history was determined by the Northern Pacific Railroad since it owned and controlled all the south shore of Commencement Bay southward into the Thea Foss Waterway. In addition, the creation of industries and shipping facilities east of the waterway was initially limited by the Puyallup Indian Reservation. To remedy the situation Congress passed the Dawes Act in 1887 that led to the ultimate alienation of most of the reservation and opened up the area to port development. In 1894, construction of the first 11th Street bridge began. The following year it was completed and provided the only way that workers could get back and forth between their homes in Tacoma and the port-industrial area. (Tacoma Public Library Richards Studio Collection C117132-3)

In 1889, even before the completion of the first 11th Street Bridge, Thea Foss had started a boat rental business along the shoreline of what would become the City Waterway. By the end of the 19th century Thea, along with husband Andrew and their three sons, had created Foss Launch and Tug Company, now Foss Maritime. This view was taken in c.1895 shortly after the construction of the first 11th Street Bridge and shows the Tacoma Hotel in the background. In 1989, the City Waterway was renamed to honor Thea Foss because of the role she played in establishing one of the largest tugboat enterprises on the West Coast. (Tacoma Public Library, General Photograph Collection, TPL-386)

Even though Tacomans anticipated rapid economic growth following the construction of the first 11th Street bridge, development in what was to become the port-industrial area was slow as this undated photograph shows. The building complex to the left is the Pacific Meat Company. In 1903, after it failed and abandoned the buildings, the property was acquired by Carstens Packing Company who developed the site into a major meat production concern. (Thomas R. Stenger)

By 1907, the Army Corps of Engineers had completed the dredging of the Thea Foss Waterway and local private planners were beginning to put forward their ideas for future port development on former Puyallup Indian land. This can be seen in a map produced that year by D.H. White.

What is shown here did not totally exist at the time since the tidelands had yet to be filled and local developers did not have the funds to carry out their dream of new industries and modern shipping wharves.

By this time, however, the Pierce/King County boundary had been shifted eastward to the original reservation boundary in East Tacoma. In the future transportation links between this newly acquired territory and the City of Tacoma would be a major concern. (Tacoma Public Library Map Collections)

Early Tacomans were willing to tax themselves when the electorate thought the endeavor important for the benefit of the city. Before 1912, when this photograph was taken, voters agreed to fund public power and water systems, as well as a park district. Later years would show them willing to fund the creation of Camp Lewis (1917) and a port district (1919). In this view the Murray Morgan Bridge is under construction. In order to keep the older swing bridge operating it was rerouted to allow the piers and trusses for the new bridge to be built.

In 1911, the Kansas City firm of Waddell and Harrington, who also had designed Portland, Oregon’s Hawthorne bridge the year before, submitted its plans for the Murray Morgan Bridge. Two years later, on February 15, 1913, local citizens gathered to watch Miss Enola McIntyre christen it by breaking a bottle of champagne on a steel girder. Originally there was a wood truss structure on the east approach. This was replaced by a concrete structure in 1957 when ownership was transferred to the State of Washington and it became part of SR 509. The vertical lift bridge was designed to ease transportation between downtown Tacoma and the port area while enabling larger ships to traverse the Thea Foss Waterway.

Once the new bridge was completed, it became the backdrop for more than one photographer showing Tacoma’s Central Business District and the buildings along 11th Street. Everyone knew that were it not for the waterway crossing linking industrial development to the metropolis it could not retain its status as the “City of Destiny.”

Tacoma’s pride and joy was the mile-long stretch of wharves lining Commencement Bay and the head of the Thea Foss Waterway. As this 1921 photograph taken by Marvin Boland shows these wharves are only connected by rail lines. Dock Street has yet to be built and there was no need to connect the Murray Morgan Bridge to the shoreline. Instead, passenger and streetcar traffic led westward from the water’s edge onto 11th Street. From there, workers could either walk home, if they lived nearby, or would transfer to another streetcar in the downtown area that would take them to their families.

During the early years of its history, the Northern Pacific Railroad refused to provide the City of Tacoma ownership of property along the shoreline. And in the 1890s, the Tacoma Council unsuccessfully tried to get a bill passed in the state legislature transferring ownership of all the shoreline to the city. In 1911, Tacoma obtained access to the waterway when a part of the McNear warehouse located just north of the first 11th Street bridge became the Municipal Dock. This became home to the “Mosquito Fleet” of steamers that carried passengers and freight around Puget Sound.

Passenger bridges leading from the Municipal Dock were the only way that travelers could get to downtown Tacoma. One ramp (shown in the photograph) led to the Murray Morgan Bridge. From there passengers could either continue walking along 11th Street, or take another route to the Tacoma Hotel. During the peak of the day with passengers getting off of or heading for a Mosquito Fleet steamer, and with workers going to and from the port-industrial area across the bridge, this part of Tacoma must have been a rather busy place during the early years of the 20th century.

Historians view the Murray Morgan Bridge as a significant early example of a vertical lift bridge. Just following its construction, bridge designer John Alexander Low Waddell wrote that “not only is it inexpensive [to build] but it is also simple, rigid, easy to operate, and economical of power.” Perhaps that was why Murray Morgan in 1949 at the age of thirty-three could tend the bridge while housed in the small structure, seen in the center of this photo, and write his history of Seattle, Skid Road. (Tacoma Public Library Boland Collection B16995)

When constructed the bridge had two streetcar lines that were electrically connected to the operations of the vertical lift span. Theoretically power could be cut to the streetcars when the lift span was in operation. The system failed on December 30, 1925 and a streetcar plunged into the Thea Foss Waterway. The crew of the Virginia V, a passenger ferry tied up at the Municipal Dock, witnessed the accident and rushed to save those on the streetcar. The Virginia V still plies the waters of Puget Sound and on occasion can be seen in Tacoma. (Tacoma Public Library General Photograph Collection G50.1-062)

The east side of the Thea Foss Waterway and the Puyallup River delta were symbols of hope for Tacomans. The slogan “Watch Tacoma Grow” was posted along the shoreline as an invitation to development. As this 1930 photograph documents, the city also wanted to publicize the availability of cheap power and placed a sign on the Murray Morgan Bridge to advertise the fact. The Wheeler-Osgood lumber mills are shown in the background.

In 1889 William C. Wheeler and George R. Osgood established a finishing mill on a small arm of the Thea Foss Waterway – originally a branch of the Puyallup River -- that currently bears their names. From that time until 1950 the firm produced a wide array of products from wood framing for windows to plywood doors and at one time was a major producer of such products in the West. Marvin Boland was able to capture a portion of the facility shown in the foreground of this 1931 photograph. Plans are now under consideration to create a marine-related commercial and light industrial development with a marina and public access to the shoreline. (Tacoma Public Library Boland Collection B23720)

During the 1930s the bridge became a demonstration center for longshoremen and lumber mill workers seeking union recognition and better wages as well as working conditions. Such was the case in May of 1935 when lumber workers walked off the job. When lumber mill owners began hiring “scabs” to take their place corporate officials convinced the governor to call out the Washington National Guard. It was their job, as they mustered on the east side of the Murray Morgan Bridge, to create a blockade. Following demonstrations and tear gas battles on the west side of the bridge, mediators were able to end the strike three months later.

The wharves below the Murray Morgan Bridge were places where historic ships would tie-up and become early-day tourist attractions. The restored U.S.S. Constitution (Old Ironsides) visited Tacoma in 1933. The destroyer U.S.S. Laffey is shown here on display at the Tacoma Municipal Dock in May of 1945. It had been a victim of kamikaze attacks north of Okinawa and had been sent to Tacoma’s Todd Shipyard for repairs. The Foss Waterway Seaport, located on Dock Street, continues the tradition of telling the story of Puget Sound historic ships. (Tacoma Public Library, Richards Studio Collection, D19533-4)

By 1946, the streetcar lines are gone and automobiles had taken their place. World War II is over and the former bustle of activity of men and women going to and coming home from the shipyards and other industrial plants is a thing of the past. Who this particular woman was, and why she was photographed here, is unknown. Even so the snapshot shows the grandeur of the bridge and a quiet time before Tacoma embarked on a new era of port-industrial development. (Thomas R. Stenger)

Even though early proponents of the Murray Morgan Bridge thought the vertical lift configuration would enable large ships to enter the Thea Foss Waterway, two small-scale swing railroad bridges located to the south inhibited the possibility. And while later Tacomans liked to think of themselves as a city of bridges the 11th Street Bridge remained the major vehicular and pedestrian link between the City of Destiny and the port-industrial area. By the end of World War II in 1945 until more modern times the structure would carry most of the workers responsible for the development of the port. (1948 Photo: Tacoma Public Library Richards Collection D34612-114)

In 1955, Japanese artist Fumiko Kimura created this image of the Murray Morgan Bridge. While it is unknown why she chose this particular subject, she believes “the purpose of art is to keep us spiritually and physically healthy.” The current owner of the painting allowed its use during the campaign to save the structure when artists were invited to “Celebrate the Bridge” through original creations. (John Butler and Fumiko Kimura)

The future of the Murray Morgan Bridge was determined less by what was happening in the port-industrial area, or even the City of Tacoma, but more by what Congress was deliberating in Washington, D.C. Of major concern in the 1950s was the need to be able to transport military units throughout the United States should there be a war with the Soviet Union. The result was the creation of a national integrated road system first proposed in a 1955 study. Two years later, the Washington State Department of Transportation acquired the Murray Morgan Bridge as a part of its SR 509 route that led north to King County. (1958 photo: Tacoma Public Library Richards Collection A113921-9)

SR 509 was a major link between Northeast Tacoma and the city’s Central Business District. By 1979 the Port of Tacoma was building new terminals and preparing for a future of container cargo facilities. Also in that year the Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation initiated a statewide survey of historic bridges to determine which should be placed in the National Register of Historic Places. In 1982, the Murray Morgan Bridge was placed in the register both because of its designers, Waddell and Harrington of Kansas City, and because it was a unique and early example of a vertical lift bridge. (Ron Karabaich)

Thea Foss once maintained her small fleet of rental pleasure boats where marinas are shown in this 1979 photograph. Tacoma’s Fireboat No.1, commissioned in 1929, was birthed below the bridge on the upper east side. One year after this photograph was taken the boat, that for almost a half-century protected the entire port alone, was placed in the National Register of Historic Places, and retired to a park located on Ruston Way. (Ron Karabaich)

The present cable-stay SR 509 bridge opened for traffic on January 1997 and concerns immediately arose as to what might happen to the then-called 11th Street Bridge. To point to its historic significance the Washington State Legislature passed Memorial 8015 in April of that year recommending that the name of the bridge should be changed to Murray Morgan in part because he had “brought the world to Tacoma, and Tacoma to the world.” The following month the Washington State Transportation Commission approved the change. Washington State retained ownership of the Murray Morgan Bridge until 2009 when ownership was transferred to the City of Tacoma. (Ron Karabaich)

The present cable-stay SR 509 bridge opened for traffic on January 1997 and concerns immediately arose as to what might happen to the then-called 11th Street Bridge. To point to its historic significance the Washington State Legislature passed Memorial 8015 in April of that year recommending that the name of the bridge should be changed to Murray Morgan in part because he had “brought the world to Tacoma, and Tacoma to the world.” The following month the Washington State Transportation Commission approved the change. Washington State retained ownership of the Murray Morgan Bridge until 2009 when ownership was transferred to the City of Tacoma. (Ron Karabaich)

When Ron Karabaich took this night view of the Murray Morgan Bridge in 2003 there was, according to one account, Peregrine falcons nesting on one of the towers thus providing another argument as to why the structure should be saved. Gradually groups of citizens, including members of the Tacoma Historical Society, formed to publicize the importance of the bridge. One of their first endeavors was to light it so that it could be seen at night. (Ron Karabacih)

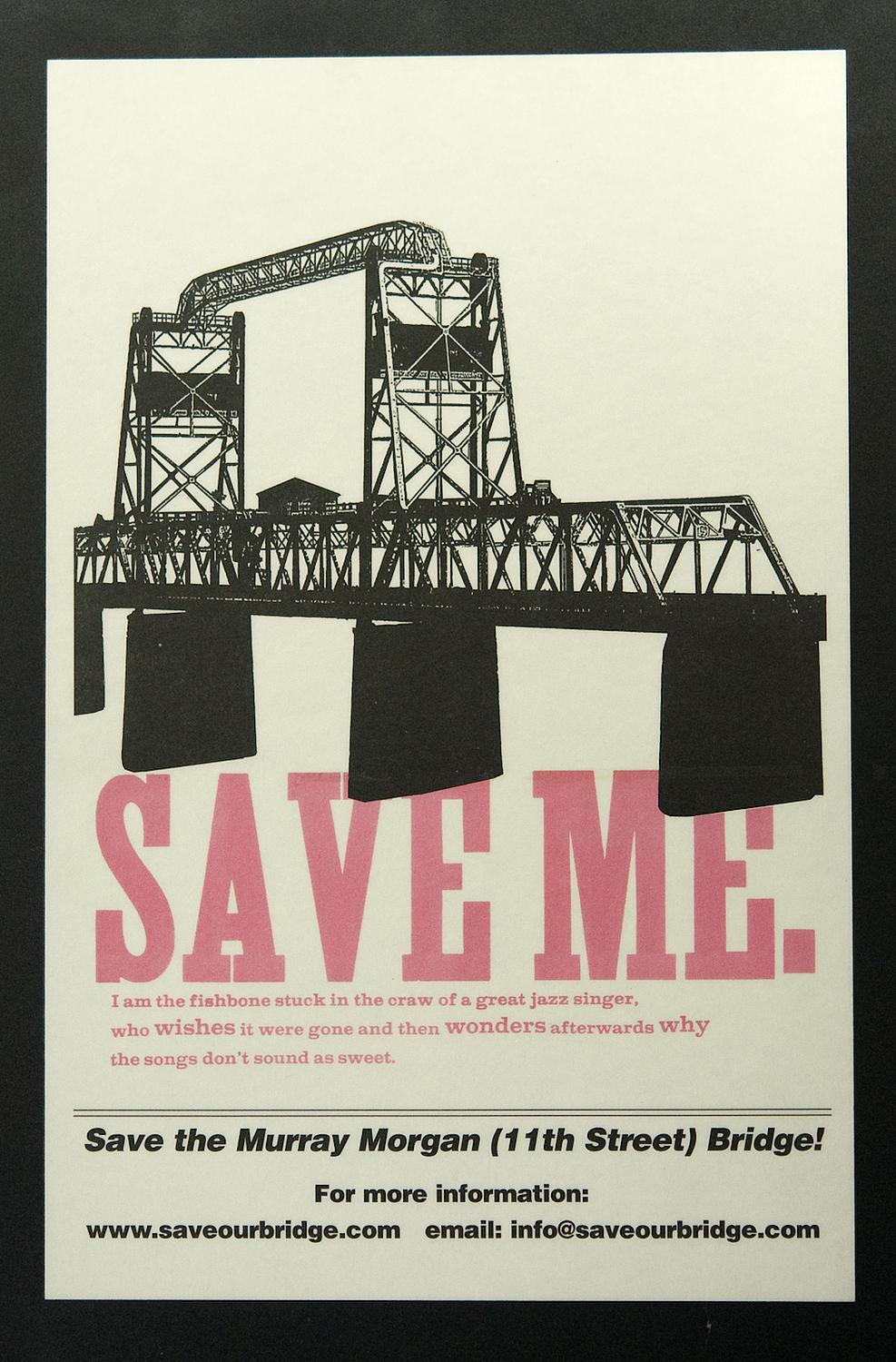

Saving the Murray Morgan Bridge was controversial. There were those who thought the structure was unsafe and should be torn down for that reason. Others simply did not like the looks of something old that clouded Tacoma’s attempts to build a modern urban environment along the Thea Foss Waterway. But, as TNT’s Peter Callaghan pointed out in his March 28, 2010 column, the Save Our Bridge advocates were able to convince Council members that it was an important link across the waterway both for future development and because it was a vital emergency route linking downtown to the Port of Tacoma. (Artist Unknown)

Saving the Murray Morgan Bridge was controversial. There were those who thought the structure was unsafe and should be torn down for that reason. Others simply did not like the looks of something old that clouded Tacoma’s attempts to build a modern urban environment along the Thea Foss Waterway. But, as TNT’s Peter Callaghan pointed out in his March 28, 2010 column, the Save Our Bridge advocates were able to convince Council members that it was an important link across the waterway both for future development and because it was a vital emergency route linking downtown to the Port of Tacoma. (Artist Unknown)

On the morning of April 19, 2011 local politicians Mayor Marilyn Strickland, Councilmember Jake Fey, previous Mayor Bill Baarsma, Congressmen Norm Dicks and Adam Smith, as well as Secretary of Transportation Paula Hammond joined in a painting ceremony to celebrate the start of the rehabilitation of the bridge and the Tacoma Landmarks Preservation Commission’s decision to paint the bridge black, its original color. Following The News Tribune’s reporting of the decision to paint the bridge black on March 24th bloggers responded both for and against the decision. One writer noted that “in 1913 they probably had the same choices as anyone who bought a model T Ford. You can choose any color you like as long as it’s black!”

On the morning of April 19, 2011 local politicians Mayor Marilyn Strickland, Councilmember Jake Fey, previous Mayor Bill Baarsma, Congressmen Norm Dicks and Adam Smith, as well as Secretary of Transportation Paula Hammond joined in a painting ceremony to celebrate the start of the rehabilitation of the bridge and the Tacoma Landmarks Preservation Commission’s decision to paint the bridge black, its original color. Following The News Tribune’s reporting of the decision to paint the bridge black on March 24th bloggers responded both for and against the decision. One writer noted that “in 1913 they probably had the same choices as anyone who bought a model T Ford. You can choose any color you like as long as it’s black!”

As of May 2011 restoration of the Murray Morgan Bridge continues. Besides painting it black to reflect the original color, its former four lanes will be reduced to two and bicycle lanes will be added. The vertical lift span will receive new mechanical and power systems, and there will be structural repairs to the supporting structure. The bridge will be back open for traffic by the end of 2012. (Ron Karabaich)

As of May 2011 restoration of the Murray Morgan Bridge continues. Besides painting it black to reflect the original color, its former four lanes will be reduced to two and bicycle lanes will be added. The vertical lift span will receive new mechanical and power systems, and there will be structural repairs to the supporting structure. The bridge will be back open for traffic by the end of 2012. (Ron Karabaich)

Contact for this web page: ndaly@cityoftacoma.org